Tags

"A General Feeling of Disorder", "A Leg to Stand On", "Awakenings", "My Own Life", "On the Move", "The Mind's Eye", 'The Many Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat", author, neurologist, Oliver Sacks, Uncle Tungsten"

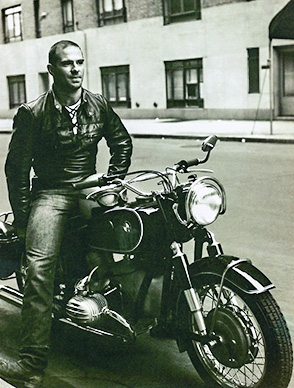

If you ‘know of’ Oliver Sacks, have read one or more of his 12 previous books, then the picture above might be a bit surprising to you.

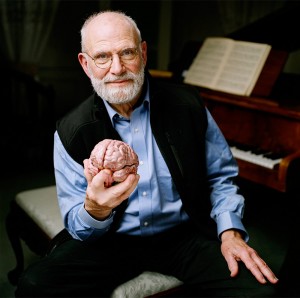

Usually, the pictures we see of this neurologist/author portray quite a different image.

More like this picture to your right:

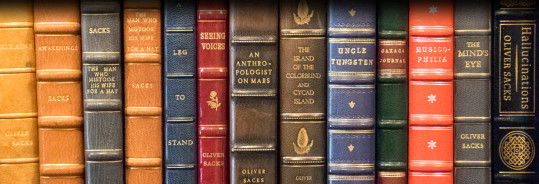

As you may know, Sacks is a prolific writer, using cases from his work with a variety of patients to describe a world that most of us do not know, a world where anomalies of the brain lead to behaviors and lives that often seem strange, at least until Sacks explains them to us.

As you also may know, Oliver Sacks is dying of terminal cancer, as he announced in an eloquent and affecting NYTimes column, My Own Life, three months ago (although since writing that piece in February, he wrote a second column in April, A General Feeling of Disorder, NY Review of Books, and seems to have ‘rallied’ and may be with us for a while longer).

I have long been intrigued by Sacks’ work, his writings, his findings, and by the man himself. Thus, when his 13th book, a memoir, On the Move: A Life, was published several weeks ago, I, of course, read it immediately.

Some of what we read in this memoir is familiar as he has written about himself previously (particularly in his Uncle Tugsten and in his A Leg to Stand On). We know he is a doctor, a scientist, an author, and above all an advocate for (our) understanding strange behaviors and listening to the lives of (his) patients.

But there is much that is new also.

He was once a weightlifter and held a title in that field.

He loved motorcycles and rode them (often at 100 miles an hour) for much of his life.

He was addicted to drugs.

He has always been an avid reader and investigator, as well as a prodigious writer. (He has kept personal journals all of his adult life in addition to his 13 books, hundreds of articles, and thousands of physician notes and reports.)

Swimming has always been a love of his life and continues to be a source of comfort for him now.

He is gay and writes about that part of his life, about his love affairs and about 36 years of sexual abstinence.

And there is much more in On the Move.

He writes openly about his family and his family relationships, including his move (escape?) from England to the US for most of his professional life.

He describes his own physical, medical, and emotional struggles, some of which he believes have made him a better physician, neurologist, and investigator.

He describes in some detail his work on the back wards of a chronic care hospital in the Bronx and how that led to his understanding of many patients who have been misdiagnosed, to some of his writing (Awakenings) and eventual notoriety, and to some controversies about his work.

Although On the Move sometimes wanders, sometimes is in need of a good editor, and sometimes is uneven — telling too much or too little, it fills in many details not previously (widely) known about Sacks. It is filled with the energy and the passions of Sacks’ life, and, as good memoirs do, let’s us understand more than we have known previously about this fascinating and unusual person.

It seems to me Oliver Sacks has always been a story teller. Virtually every one of his 12 previous books have been at their core his stories about his patients, and, occasionally, about himself. But he is also a teacher, and his stories always seem to have lessons for his readers.

In On the Move the stories are all about himself, and it’s an honest, humorous, and sometimes painful memoir, and an accounting of a life.

liz Frost said:

Thank you for the update on Larry’s favorite author.